AFRICA REGIONAL OVERVIEW 2025

Trends in the repression of freedom of expression across sub-Saharan Africa throughout 2025 illustrate a worrying and continuing deterioration of civic space across the region. The 2024 report CIVICUS Monitor: Tracking Civic Space rates civic space in 43 out of 50 countries in the region as obstructed, repressed or closed. Cabo Verde and Sao Tome and Principe are rated as the only countries whose civic space is open, while countries like Mauritius, Namibia and Seychelles, which previously stood out as positive examples for civic freedoms, moved down to a categorisation of ‘narrow’. A common thread among low-rated countries is authorities’ disregard for national constitutional commitments to democratic governance, and outright contempt for their regional and international human rights obligations.

Conflict and war

In Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Nigeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Mozambique, the dynamics of pervasive armed conflict and war continued to destroy the foundations necessary for the exercise of civic freedoms and human rights, including the right to freedom of expression. The UN estimates that 12.3 million people, a quarter of Sudan’s population, were internally displaced at the end of the year, with a UN expert highlighting increasing risk factors and indicators of genocide in the Darfur region. An additional 2.5 million Sudanese refugees and asylum seekers were being hosted in neighbouring countries.

A resurgence of conflict in the DRC has led to mass casualties. Large-scale forced displacement over decades has led to almost seven million internally displaced persons to evacuate to the North and Western parts of DRC and more than one million fleeing the country to seek refuge in neighbouring countries. With reports of large-scale sexual and gender-based crimes by combatants and their allies, including rape and murder of women and girls, emerging amidst weak regional and international responses to the crisis, the renewed deterioration in January 2025 of the security, human rights and humanitarian situation in Goma and elsewhere in the country is bound to persist.

Weaponisation of the rule of law

The ongoing tide of rising authoritarianism across the region is intimately linked to the overall constrained civic space, particularly the relentless attacks on freedom of expression in many African countries. Repressive governments continued to weaponise rule of law and justice systems against dissenting writers, journalists, artists, social media commentators and peaceful protesters.

However, weaponisation of legislation and rule of law is by no means a new phenomenon in the toolbox of repressive governments. Paradoxically, since independence, virtually all countries in sub-Saharan Africa retain colonial era statutes originally aimed at silencing anti-colonial sentiment and expression, including critical commentary about government officials. These often vaguely-defined laws typically criminalise insult and defamation as well as prohibiting ‘offences’ against ‘public order’; ‘national security’; ‘public morality’; ‘disturbance of peace’; and ‘incitement’, among others.

Such laws are frequently used to criminalise and restrict the right to peaceful protest, while ‘public morality’ legislation is used to silence expression on topics such as gender and sexual orientation, deemed taboo by dominant social and cultural power systems. Furthermore, three global events: the post 9/11 so-called ‘Global War on Terror’ and the spread of anti-terror legislation that followed; the rise of internet-enabled crimes leading to the necessity of cyber-security policy and legal frameworks; and emergent needs to counter online and offline misinformation, disinformation and hate speech – all ironically presented repressive governments additional fiat to supress free speech rights.

In Eswatini, in August, a Supreme Court judgment not only upheld the colonial era Sedition and Subversive Act 1938, but also overturned a progressive 2016 decision that had struck down controversial provisions of the broad and vaguely worded Suppression of Terrorism Act No 11 of 2008, which authorities have used since its enactment to curtail freedom of expression by labelling dissenters, journalists, and activists as ‘terrorists’. This decision is having dire consequences for freedom of expression, as shown by the fate of Mduduzi Bacede Mabuza and Mthandeni Dube, Members of Parliament who were sentenced to decades in prison on 15 July 2024 for advocating for democratic reform during June 2021 protests.

In what would otherwise pass for relatively good news, in July 2024, President Ndayishimiye of Burundi assented to Law No. 1/21 of 12 July 2024, which partially decriminalises press offences by providing for fines in place of prison sentences for ‘offences’ including ‘insult’, ‘slanderous denunciation’ and ‘public outrage against good morals’. While the amendment was welcomed by journalists’ organisations, legitimate concerns about the law remain, due to the criminal not civil nature of the offences. The 13 July arrest and two-day detention of journalist Pantaléon Ntakarutimana, a day after the new law was passed, for allegedly publishing false information illustrates the continued threats faced by media workers despite the promise of this new legislation whose objective was to put Burundi on the same page with countries that uphold democracy and press freedom.

On 9 October 2024, Cameroon’s Minister of Territorial Administration Paul Ntanga Nji issued a communiqué forbidding all media debate on President Paul Biya’s health, following speculation that the then 91-year-old president may have died. The decree stressed that ‘offenders’ against the decree would face the full force of the law and tasked governors with forming ‘monitoring cells’ to identify those who write ‘tendentious comments’ online and in private media, threatening them with prosecution. Despite Nigeria amending its Cybercrimes Act in February to remove articles that violated press freedoms, according to Reporters without Borders, authorities arrested, prosecuted or detained at least eight investigative journalists under the pre-amendment law in retaliation for their legitimate journalistic work. Malawi also targeted journalists using cybercrimes laws.

Persecution of writers and journalists

PEN International supported African writers and journalists facing persecution, including threats to physical safety, arbitrary arrest and judicial harassment by authorities in Eritrea, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Ghana, Togo, Uganda, Gambia, and Zimbabwe; displacement due to armed conflict in Sudan; assault, displacement and denial of livelihood options because of their non-binary gender and sexual identities in Nigeria and Uganda; and imprisonment after writing and publishing a book critical of the authorities in Mali.

In Equatorial Guinea, writer, academic and LGBTQI rights activist Trifonia Melibea Obono Ntutumu has been a target of intimidation and harassment by authorities since she published her novel La Bastarda in 2016. The book, which explores women’s rights, gender and sexuality, is banned in Equatorial Guinea. She left her country fearing for her safety, but continues to receive threats abroad.

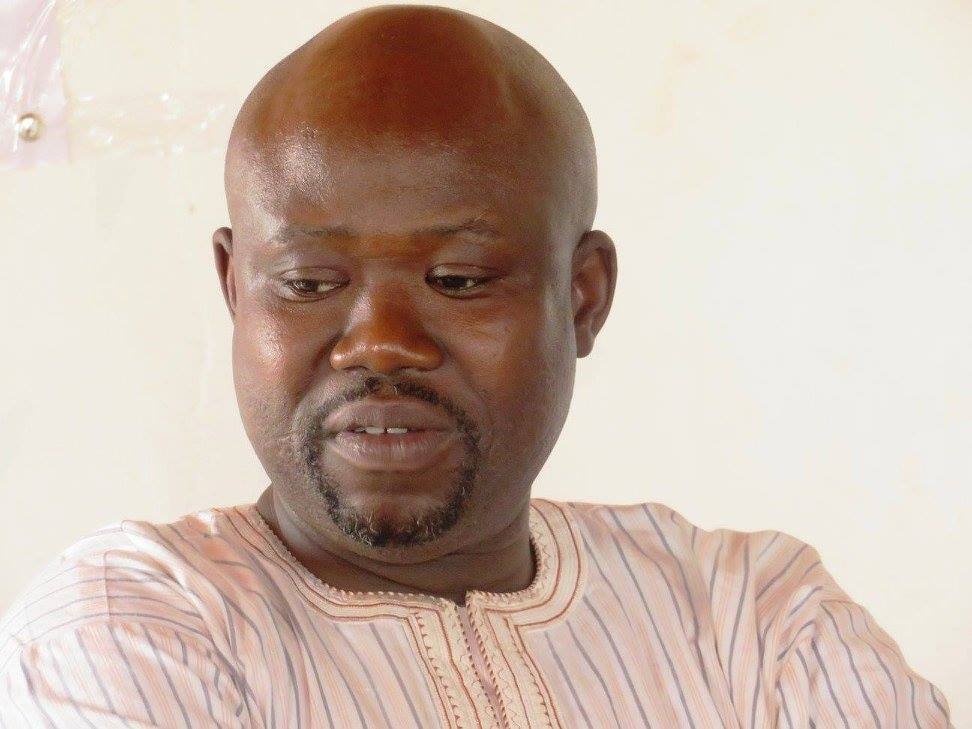

In Mali, non-fiction author, academic, activist, and publisher, Professor Étienne Fakaba Sissoko was arrested in March 2024, and charged with ‘harming the reputation of the state’, ‘defamation’ and ‘dissemination of false news disturbing the public peace’ in connection with his 2023 book Propagande, Agitation, Harcèlement: La communication gouvernementale pendant la transition au Mali (Propaganda, Agitation, Harassment: Government Communication During Mali's Transition) which criticises the military government. He was subsequently convicted and sentenced on 20 May 2024 to two years in prison, with one year suspended, and a fine of XOF three million (about USD 4800) for ‘damages’ to the state. The conviction was upheld on appeal (see Mali section below). PEN International continues to call for the unconditional release of Sissoko and offer solidarity support to his family.

Journalists also continued to suffer persecution.According to CPJ’s annual prison census, a total of 34 journalists and media workers were held in prison across sub-Saharan Africa at the end of the year. These include 16 journalists, among them writers and poets imprisoned by Eritrea without trial and incommunicado for the last 23 years (see Eritrea section below). Other countries jailing writers include Ethiopia (6); Rwanda (5); Cameroon (5), with Burundi and Senegal jailing one journalist each. Furthermore, according to IFJ findings, 10 press workers were deliberately killed in connection to their work in Sudan (6); Somalia (2); Chad (1) and DRC (1).

Transnational repression

Beyond national boundaries, the rise of transnational repression is a major area of concern in the region. A Freedom House report identified Uganda as a leading perpetrator following the unlawful abduction in Kenya and forced return to Uganda of 36 Ugandan activists attending a workshop in Kenya in July 2024. In October, the abduction, disappearance and refoulement of seven Turkish asylum seekers and abduction and forced return to Uganda of opposition leader Kizza Besigye in November illustrate Kenya’s growing role in the worrying global trend of governments colluding to enable transnational repression. Other countries in the region reported to be perpetrators in transnational repression include Rwanda, Equatorial Guinea, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Online restrictions continue

According to Surfshark, sub-Saharan Africa witnessed 17 instances of internet restrictions during the year in eight countries: Mozambique (8); Kenya (2); Senegal (2); Nigeria (1); Chad, (1); Comoros (1) Mauritius (1); and Sudan (1- an almost two-year-long instance related to the ongoing armed conflict). These restrictions aimed to limit social media and online information exchange and public debate during periods of political turmoil, particularly in relation to election disputes, conflict, and protest.

In December, talks between Uganda and Meta were underway to restore access to Facebook, blocked by presidential order since 2021 (except via VPN) after a fallout over deletion of ruling-party associated accounts that Meta had found violated the platforms terms. Although a positive step, Uganda’s record of repression of online expression, particularly on X and TikTok under the draconian 2011 Computer Misuse Act is highly likely to continue on Facebook if restored.

Repression of peaceful protest

The right to peaceful protest is intimately linked to the right to freedom of expression. Following widespread youth-led public protests against proposed tax increases amidst government corruption and a cost-of-living crisis, authorities in Kenya carried out a brutal crackdown on perceived online and offline communicators, organisers and mobilisers of the peaceful protests. Over 60 protesters were reported killed through unlawful actions by security forces and more than 1200 arrested. The second half of the year saw 82 abductions, enforced and involuntary disappearance officially confirmed, with 29 people still missing. While some came out alive, others were found dead. Kenya’s response to dissenting social media users brought to the fore authorities’ systematic use of unlawful digital surveillance, reportedly with the alleged aid of the largest telecommunications company in the country, to repress free speech and violate human rights with impunity.

Other countries where authorities repressed peaceful protest include Nigeria, in the context of protests calling for good governance; Senegal, following attempts to postpone presidential elections, and Mozambique, in connection with disputed election results.

Challenging the silencing

The Case List’s grim reading highlights how authorities across Africa continued to silence critical voices through the use of arbitrary arrest and detention; prolonged pre-trial detention; malicious prosecution and imprisonment; violent disruption of peaceful protests; abductions and enforced disappearances; extrajudicial killings; and arbitrary restrictions that censored online expression. Underlying these violations is an overall climate of intolerance of officials to public exposure, criticism, censure and protest over management of public affairs, as well as systemic impunity for perpetrators.

To push back on the growing repression across the region, PEN International spoke out through regional and international advocacy, including through public statements, coordinating solidarity actions and writing open letters to authorities in support of writers at risk. We highlighted our major concerns regarding freedom of expression at the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights and supported a collaborative project focused on promoting the protection of the right to write in five African countries as a strategic step towards strengthening our advocacy at national and regional platforms, mobilising writers and other relevant state and non-state actors to promote and defend freedom of expression.

GOOD NEWS

Mubarak Bala, the president of the Humanist Association of Nigeria was freed by the High Court in Kano on 19 August 2024. He was arrested in 2020 for posting ‘blasphemous’ content on Facebook and sentenced to 24 years’ imprisonment in 2022, later reduced to five years on appeal. PEN International and PEN Nigeria joined Humanist International and other organisations and individuals in a joint appeal for his unconditional release in 2021.

Authorities unconditionally withdrew a criminal and civil prosecution instituted by the president of Gambia against journalist Musa Sheriff, president of PEN Gambia and his colleague Momodou Justice Darboe in retaliation for their journalistic work after public pressure and private outreach to the presidency by press freedom and human rights groups.

Similarly, PEN International was delighted that the prosecution of PEN Togo president, Marthe Nounfoh Fare ended after authorities withdrew frivolous charges brought against her in retaliation for a video she had posted and commented about on her TikTok account.