ASIA PACIFIC REGIONAL OVERVIEW 2025

In countries across the region, the right to freedom of expression is increasingly under pressure. Governments continue to misuse laws and judicial systems as a tool to silence peaceful expression by subjecting writers, cultural figures, journalists and other dissenting voices to censorship, harassment, arbitrary arrest and long-term imprisonment.

Pervasive use of long-term imprisonment

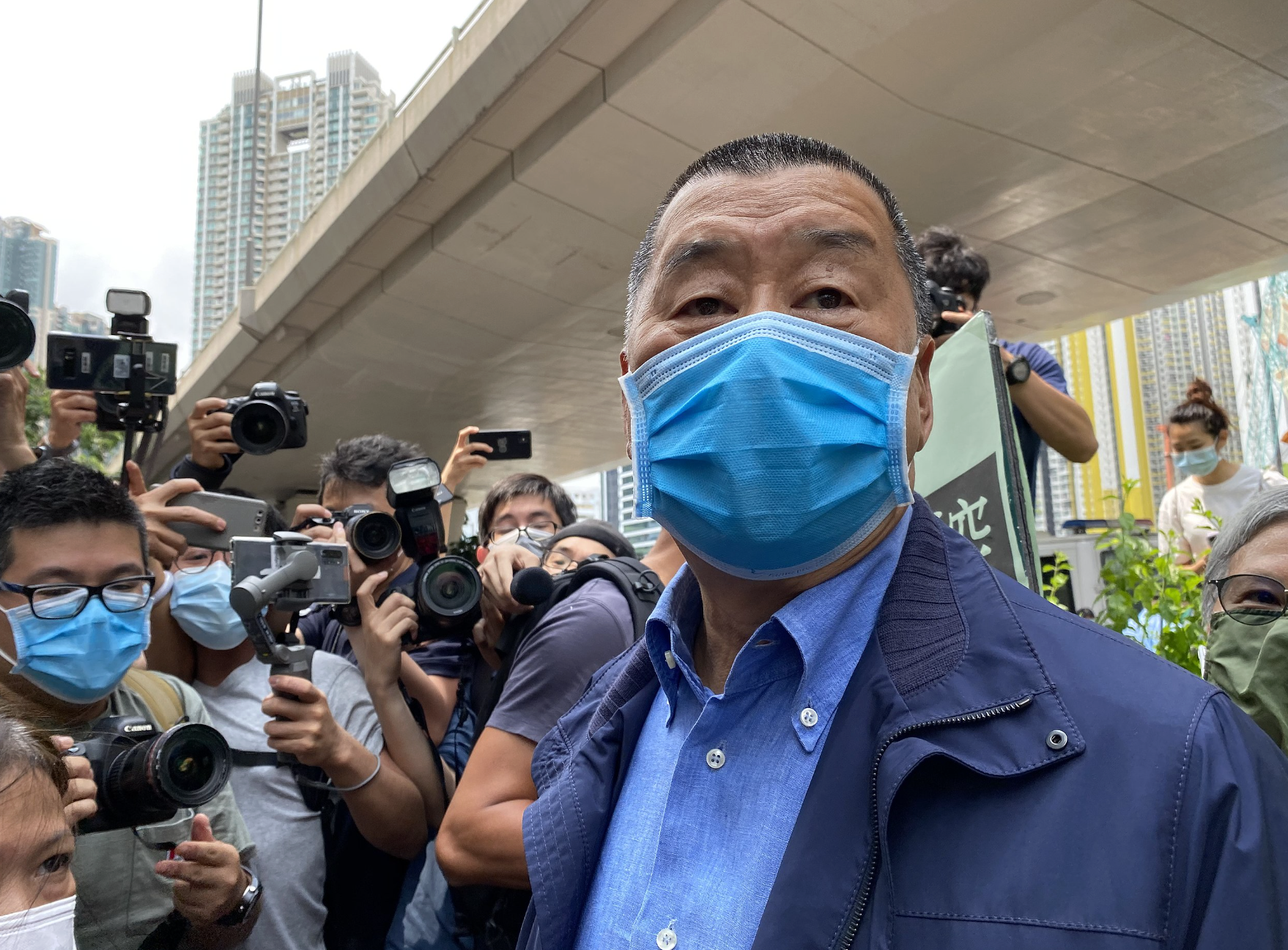

In China, throughout the year government authorities continued in their unrelenting subjection of writers, poets, academics and bloggers to long-term prison sentences (see China section below). In February, writer Yang Hengjun was handed down a suspended death sentence over two and a half years after a closed-door trial. Despite China’s long-established reputation as the world’s leading jailer of writers and journalists, the severity of the sentence marked a shocking escalation in the Chinese government’s worsening crackdown on dissenting voices, drawing condemnation from PEN Centres around the world. In November, the national security trial in Hong Kong against writer and media publisher Jimmy Lai resumed, more than four years since his initial arrest in August 2020. If convicted under the draconian National Security Law, Lai faces a potential life sentence for his journalism and activism. Government authorities continue to engage in the systematic cultural repression of Uyghurs, Tibetans and other ethnic minority communities, illustrated by the ongoing life imprisonment of Uyghur academics Rahile Dawut and Ilham Tohti, and the long prison sentence being served by Tibetan writer, Go Sherab Gyatso.

In Myanmar, dozens of journalists, writers and others are currently imprisoned on trumped-up charges relating to their peaceful criticism of the military junta and its coup that toppled the country’s elected government in February 2021. Among those who remain imprisoned on long sentences is writer and activist, Wai Moe Naing, who is now serving a combined sentence of 74 years in prison (see Myanmar section below).

Meanwhile in Thailand, poet and activist Arnon Nampha is serving a combined sentence of 18 years and 10 months in prison, following his conviction in 2023 and 2024 of six counts of violating Thailand’s notorious royal defamation law, which can result in a maximum sentence of 15 years in prison per charge. With eight further royal defamation charges pending, Arnon faces a potential maximum sentence of almost 140 years in prison if convicted on all counts (see Thailand section below).

Overlong prison sentences continue to be routinely imposed on government critics in Vietnam, including blogger and journalist Nguyen Vu Binh, sentenced to seven years in September after he was convicted of spreading anti-state propaganda. The same charge was brought against writer and activist Pham Doan Trang, currently serving a nine-year prison sentence following her conviction in 2021 (see Vietnam section below).

Shrinking space for online expression

The internet plays a vital role as a space for expression, particularly in countries where print media is subject to various forms of censorship. This has led to the propagation of vaguely-defined legislation, ostensibly designed to counter harms caused by mis/disinformation and hate speech, but which all too often is used as a means to censor criticism of the government. In China, the existing internet censorship regime, commonly referred to as the ‘Great Firewall’, was supplemented by new regulations. These form part of a ‘new literary inquisition’, to control online discourse by impeding internet users’ ability to circumvent the country’s censorship apparatus through the creative use of language and wordplay, part of China’s rich cultural and linguistic heritage.

New regulations were also imposed in Vietnam in December under Decree 147, providing authorities with expanded powers to block social media accounts and to compel foreign organisations, including websites and online magazines, to provide detailed user data. As noted in a joint report submitted for Vietnam’s UPR by PEN International, Vietnamese Writers Abroad PEN and PEN America, these measures risk imposing a considerable, chilling effect on online expression in the country by enhancing authorities’ ability to identify individuals engaging in online expression.

In Malaysia, despite some positive developments, including plans to formally implement the right to access information legislation, parliament in December passed amendments to the 1998 Communications and Multimedia Act: providing authorities with analogous powers to those found in Vietnam, which undermine users’ right to privacy and risk imposing a similar chilling effect on online expression. These expanded powers include the ability to carry out warrantless searches and seizures of data from service providers and to compel social media platforms to disclose user data without prior court approval.

In India, the government used the Information Technology Act to block fact-checking websites Hindutva Watch and India Hate Lab, which play an important role in tracking online hate speech, though the founder challenged the blocking orders in court; proceedings were ongoing at year end. The indiscriminate blocking of websites, part of a worrying trend in the arbitrary blocking of information that may be critical of the government or its policies, amounts to a form of pre-emptive censorship.

Internet shutdowns are another form of censorship that continues to be used by governments to impede the transfer of information for entire populations indiscriminately. This deliberate and indiscriminate act of blanket censorship is frequently implemented during times of conflict or heightened tension, as a means to conceal the perpetration of state violence and other gross human rights violations. In Myanmar, internet shutdowns, and other restrictions designed to limit individuals’ access to the internet, continue to be deployed in areas of active conflict as a means to prevent individuals from sharing information on atrocities committed by the military junta.

In Bangladesh, the former government imposed a nationwide internet shutdown on 18 July that lasted for several days as the country was gripped by the brutal use of state violence against student-led demonstrators protesting against socio-economic grievances, resulting in as many as 1,400 killed in the space of 46 days, including several journalists.

Internet shutdowns were also imposed for several weeks in Pakistan’s Balochistan region while the authorities carried out mass arrests of demonstrators who sought to draw attention to human rights violations carried out against the region’s marginalized ethnic Baloch minority.

Freedom of expression at a time of conflict and crisis

The intersection of humanitarian and human rights crises can have a devastating impact on the right to freedom of expression. In countries gripped by a combination of authoritarian rule and crisis, writers, journalists and others can find themselves unable to support themselves due to the risk of persecution for their writing, forcing them into a perpetual cycle of fear and destitution. PEN International continues to provide often life-saving support to those at greatest risk.

In Afghanistan, the country’s worsening humanitarian crisis has been compounded by the Taliban’s unrelenting and increasing efforts to silence women and girls through overwhelming levels of restrictions impacting every aspect of their lives, denying agency and dignity to a generation of women and girls. Writers, poets and journalists still in Afghanistan continue to face significant threats of arbitrary detention, torture and enforced disappearance for their writing or online expression, while many of those who have fled to bordering countries now face a life of abject precarity, including increased risk of deportation.

For those in Myanmar, almost four years of the military junta’s rule by terror has left the country ravaged by violence and destruction, exacerbated by widespread restrictions on all forms of expression, including killings of journalists. The resulting situation has forced dozens of writers and journalists to flee across the border to Thailand to escape persecution and destitution, many of whom now struggle to find security or shelter in exile and are at active risk of deportation back to Myanmar.

Even when peace processes are underway, freedom of expression often remains at risk. In the Philippines, the use of ‘red-tagging’ – accusing individuals of being communist sympathisers – continues to be used by the current government and its proxies, facilitated by social media platforms such as Facebook, as a means to silence and intimidate journalists, writers and others expressing critical views towards the government or its military, including Amanda Echanis (see the Philippines section below). Red-tagging first surged under former President Rodrigo Duterte after the collapse of peace talks with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). Those who are ‘red-tagged’ are at heightened risk of persecution, including arrest and murder. Following a visit in February, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression recommended that the government denounce the practice. She also highlighted the ongoing impunity for the killing of over 100 journalists in the last 30 years, as well as concerns regarding ongoing killings, recommending measures to protect journalists and human rights defenders. In May, the Supreme Court declared that ‘red-tagging’ amounts to a threat to people’s life, liberty and security.

Arbitrary detention and harassment

In all too many countries across the region, vexatious legal cases continue to be deployed as a means to silence critical voices. In the Philippines, journalist, writer and Nobel laureate Maria Ressa continues to be the target of a long-running campaign of lawfare despite having secured a series of significant legal victories, including the dismissal of five bogus tax evasion charges, and the overturning of a shutdown order in July 2024 that was issued against the news organisation she co-founded, Rappler (see Philippines section below).

In Bangladesh, following the August collapse of the Awami League-led government in the wake of the student-led protests and the emergence of an interim government led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, journalists and others alleged to be sympathetic towards the former government have been questioned or detained in apparent retaliation for their expression, with over 160 journalists stripped of their press accreditation. In Cambodia, investigative journalist Mech Dara was detained in October and accused of attempting to cause ‘social disorder or confusion’ over a since-deleted social media post. Released on bail, he is likely to face trial.

In India, writers Arundhati Roy and Sheikh Showkat Hussain faced renewed threat of legal proceedings in 2024 over speeches that occurred over 13 years previously. In November, journalist Mohammad Zubair was targeted with a criminal complaint in connection to his work to counter misinformation on social media. The United Nations Human Rights Committee included PEN International’s concerns over the country’s deteriorating freedom of expression environment in its Concluding Observations in India’s periodic state review under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

In China, writers, bloggers and others continue to be subjected to arbitrary arrest and detention for ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’, which is routinely used to harass dissidents and others who criticise the government. In September 2024, citizen journalist Zhang Zhan was re-detained on the above offence just four months after she was released having served a four-year sentence for the same offence in retaliation for her reporting on the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan.

Similar patterns of harassment take place in Vietnam, including the abduction and arbitrary detention of blogger and activist Danh Thi Hue, who was interrogated over her social media content and ordered to cease posting online content critical of the government.

Good news

Among the positive developments in the region is the Malaysian authorities’ decision in April to close the case against writer Uthaya Sankar SB, almost two years after an investigation was first opened over a comment he posted on social media. In May, writer and editor Prabir Purkayastha was released on bail after India’s Supreme Court declared his arrest to be ‘invalid’. In Bangladesh, the long-running probe against photojournalist Shahidul Alam was suspended in November, with the interim government also announcing its intention to repeal the repressive Cyber Security Act. In December, PEN member Zholia Parsi was awarded the Martin Ennals Prize in recognition of her selfless advocacy for the rights of women and girls in Afghanistan.