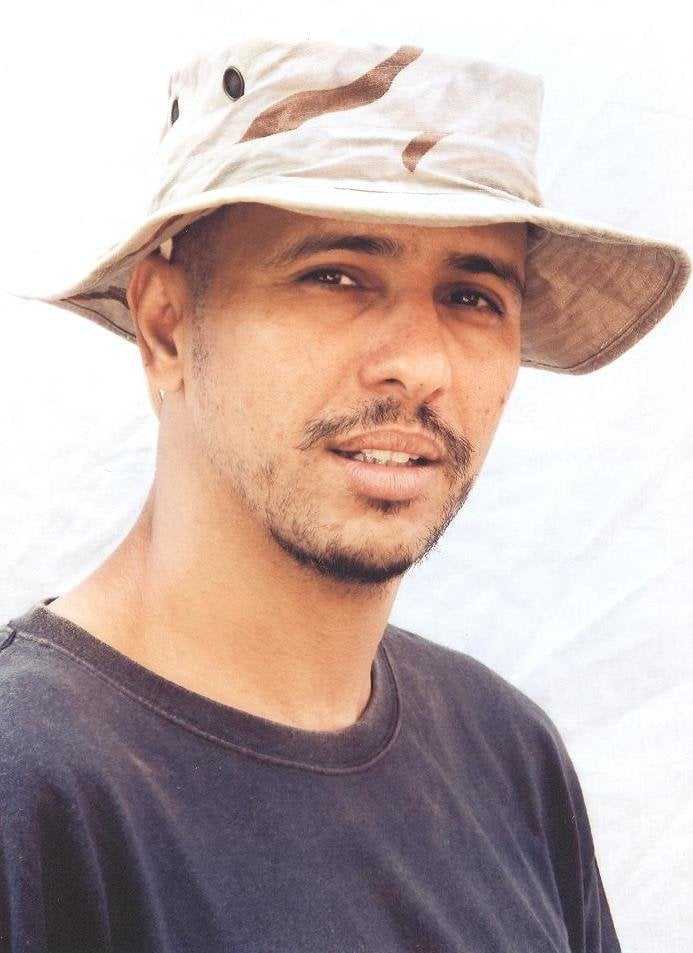

Life outside Guantanamo Bay: an interview with Mohamedou Ould Slahi

Photo: CC BY-SA 3.0

Mohamedou Ould Slahi was born in Mauritania in 1970. In 2001, at the behest of the United States, he was detained by Mauritanian authorities and rendered to a prison in Jordan; later he was rendered again, first to Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan, and finally, on August 5, 2002, to the U.S. prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, where he was subjected to severe torture. In 2010, a federal judge ordered him immediately released, but the government appealed that decision. In 2015 he published Guantanamo Diary, his account of the 13 years he had spent incarcerated within the military prison. He was cleared and released on October 16, 2016, and repatriated to his native country of Mauritania. No charges were filed against him during or after this ordeal.

Mohamedou spoke with Nael Georges, Middle East and North Africa Programme Coordinator at PEN International.

This interview is also available in Arabic.

By the time you heard that you were being released, you had been detained for over 14 years in Guantanamo Bay. How did you feel when you heard the news?

In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful. First, allow me to thank you, Mr. Nael, and thank PEN International for giving me the opportunity to talk to you.

It was surreal. I always talk about that moment. I was at Camp Sacks. I specifically remember being in Hotel Block. I recalled when the captain had come and peeked in on me through the little window, which they used to pass food to me. She smiled and said: “Do you know you are going home?” I replied: “No, I do not.” Smiling wide, she added: “Yes, you are going home.” It was our first encounter, as she got recently transferred to Guantanamo after a change of rotation. I started thinking. I don’t know why. I didn’t want to get excited over the news and disappointed afterwards. The news was plausible, but not confirmed yet. Sometimes they tell people they are going home but in the end, they don’t. And so, honestly, the situation was very exciting and surreal. It was as if someone had told me I would be going to Mars or Jupiter the next day. To me, getting released was like traveling to another planet.

You were finally released in October of 2016. How have you gone about trying to rebuild your life? What have you found to be the hardest aspect of adjusting to a new life outside of a six-foot by eight-foot prison cell?

Almost everything was banned in prison. Everything. Talking was forbidden. Communication was forbidden. No internet. No phones. You weren’t allowed to discuss anything or write what you wanted. If you wrote a letter in which you mentioned something the guard did not want, or in which you gave specific details about your situation, the letter would never leave the prison walls. If your parents sent you a letter that conveyed news the US government did not want you to know, you would never receive it. You couldn’t choose the movies or TV programs you were shown. When I reached home, my parents gave me a small smartphone, with which I could watch whatever I wanted. Ironically, I just wanted to search for the things I used to listen to in prison. I wanted to listen to the music I listened to by chance in prison and watch the movies they allowed us to watch. I searched for these because they were comforting and familiar. All I knew was a life behind bars. I started looking for Polish movies although I did not understand that language. I looked for them, nonetheless, only because I watched them while I was prison. I searched for things that I used to hear on the guards’ radio and things they would allow us to listen to, like rap music. I used to search for those things. I had also a major problem in dealing with people. It became a problem because, for instance, I started going into the house without closing the door behind me. Although I am known for being a man of morals, I would get angry really quickly when talking to people. Recurrent dreams about going back to prison kept haunting me. Every time I got into a room, I had the urge to reorganize it the same way as my Guantanamo Bay cell. I wanted to have the Guantanamo Bay cell back again and rest while watching the same movies we had been allowed to watch. I wanted nothing new. Honestly, freedom is important, but the only thing that bothers me still is that I haven’t got my freedom yet. I am a human being who wants his freedom, and I want it by peaceful means. I don’t believe in violence, and I think that nothing good comes of violence. I am so happy for getting this freedom and I hope for it to be complete.

What help did you have after you were released from Guantanamo?

The government didn’t offer any help. Socially and legally, I was honestly surprised by the overwhelming number of letters and emails I received from all over the world. I realized that the world was not divided into Arabs, Europeans, Chinese, but it was only divided between good and indifferent people. This is the world. People from all religions, cultures and races supported me, not because I am Mohammad. I am a poor unknown Bedouin; my father died when I was young. People who stood by my side and helped me were noble and good, and they believed in humanity and morals. I am thankful for that and for their support. I shall not forget that, including PEN's support. PEN backed me and spent a night reading and talking about my book while I was in prison. I didn’t know of that night until after my release. I kept going into YouTube to listen to it time and again. I still have it on my hard drive, and it still moves me to tears sometimes. People read and don’t understand what was removed by the government, but I laugh because, on the whole, I know what was removed.

You were repeatedly tortured whilst you were held in Guantanamo. What kept you going?

Honestly, I don’t know how to answer this question. I have never taken these violations and offenses personally. As a matter of fact, they were more like an insult to all people. Whoever abuses one person, they are abusing the whole of humanity. According to our culture and to the Quran: “If anyone killed a person not in retaliation of murder, or (and) to spread mischief in the land – it would be as if he killed all mankind, and if anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of all mankind.” I say I was not abused, but my government, my country and my rights as a person were. The human being deserves respect only because he is human. He does not need a PhD, nor does he need to be a prince or a king or a member from a royal family to be respected. They need only be human. I have always asked myself why. That question has always helped me. The other reason is that I like to know things. I am curious by nature, and I want to understand everything. They didn’t care about my thoughts or about what troubled me. They said they wanted to do things to me, and that was convenient to me in order to know people as they truly were. I play the role of a psychic. You will never get this kind of chance because people see you as a normal person. They don’t tell you what they think because they respect you and weigh their words before they speak in your presence. With me, on the other hand, they don’t act this way. Honestly, this makes me happy because I get to seize an opportunity that is not usually given to a writer. I had always thought and known that I would write all these things.

In those moments, did you allow yourself to hope that you would be free one day?

Absolutely. I deserve freedom just like any other human being in the world, especially in our region. Dear brother, am I less human than a Danish? Am I less human than a German? Why does a German get their rights automatically without having to write a poem or an article in which they praise the president or the king in order to get their rights? I want to get my rights without praising anyone and humiliating myself. I want my rights and those of all the citizens in this region. These rights are truly violated. I want to get them just like any other German, Danish, British and American. Why does the United States, for example, have no right of confiscating the Americans’ passports in the US, but have all the right to interfere in the provision of my Mauritanian passport? There should be an answer to this question. It is not only my problem, but it is other people’s as well.

We are experiencing a hideous phenomenon here in the Arab world: extremism. It is fuelled by raising youth to think they don’t have any value or rights. Whatever they do by peaceful means, they will fail to get anywhere. This is not PEN’s or Britain’s responsibility. This is our responsibility first and foremost. Nonetheless, when we reach powerful governments, the US people, organizations, PEN and other organizations that defend cultural and human rights, let them stand by our side, especially liberal governments: let them stand by our side, the side of the people. This is what liberals want: freedom for people living in the Arabian Gulf, Africa and the Maghreb. I have met Americans; they love freedom. I have met Americans from both political sides; they both want and love freedom, and they do not believe in dictatorships.

Did you write before you were imprisoned?

I did. When I was a little boy, I used to write short stories. We didn’t have a TV at home because my big brother forbade it after my father’s death. I used to watch TV at my friend’s house, and we only watched football. I used to have a whole host of books, like One Hundred and One Nights, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, Agatha Christie, Sherlock Holmes, not to mention books about Islamic and Arab heritage. I had a great number of books. I liked to write, and my father used to write poetry. The cultural space was there even though we were Bedouins, belonging to a Bedouin culture. I always used to write little notes that I find embarrassing when I look back at them now.

Was writing Guantanamo Diary in some way an act of faith that you would be set free? Did you have any expectation it would be read in your lifetime?

My Guantanamo Bay diaries were like “screams in the dark”, as they say, because I was not allowed to talk and give my opinion or say anything that was prison-related. I said to myself that this was my chance to say something. I was in a court where I wasn’t allowed to defend myself. They said that in reality I should be sentenced to death, but that I’d be serving only thirty years because the United States was a merciful country. If I collaborated with them, I would “only” be sentenced to thirty years in prison. What kind of mercy is this? Undoubtedly, this kind of deal is considered a good one, according to US standards of justice. In fact, writing was a way to tell people that I was innocent. Indeed, I strongly believed that my diaries would see the light, but I have never thought they would be kept for four years with intelligence agencies, and never thought that the battle of justice to get them out of the dark and into the hands of the readers would take so long.

As for the second part of your question, I repeat and say, yes, I had a deep belief that they would be read while I was still alive.

How did you write? How did you find the materials you needed?

First, they gave us pens and papers to write to our parents. After a few weeks, everyone else got their replies from their families, but I didn’t get any. Instead, I was handed a letter written by the intelligence agencies as being from my parents, but I knew my parents’ handwriting and ideas, so I returned it to them. I knew that all my letters would only be read by the intelligence agencies, so I was communicating with them by writing to my parents.

Second, they allowed me to write a letter and took the pen back. However, some of my cellmates were granted the permission of keeping the pen with them. I would steal these sometimes along with some papers to write. I started writing in Arabic about various things in various ways, like poetry. Then, I went on writing in Arabic, French and German. I wrote also in English as a way of learning. One of my inmates was British and he used to teach me the language. His name was Bisher al-Rawi. Another inmate, who was Australian and whose name was David Hicks, taught me the language as well. I helped non-Arabic speakers to learn the language because I used to teach Arabic and the Quran. That is why I used to write. I wrote some poetry as well along with my diaries. The guards found out that I was illegally keeping some papers, so they kicked me out of my cell and took all my papers and belongings. My second attempt, which turned out to be successful after years in prison (around four years), was when I met the lawyer Ms. Nancy Hollander and her team. I started writing letters to them in a diary format. I used to number them. I would write and write, then recall the last number, and so on. In a matter of three months, I wrote all my diaries, as you see in the book.

Why did it take 10 years to publish your book Guantanamo Diary?

The government denied the publishing of my book. At first, they gave me the permission to write to my lawyer. I thought I was entitled to communicate with my lawyer in a secure way, but not in Guantanamo Bay. There, I could tell the lawyer everything without her having the right to take anything home with her or use my words publicly to defend me. If the lawyer wanted so, she had to get a government approval. When I reached 466 pages, the lawyer decided to get them out through the secure room. They refused, citing a threat to national security. From that moment, the legal battle started and remained for an ongoing number of years until the book got out with a lot of editing, as you can see. I knew that the book had been printed when I was in prison, but my request of getting a copy was denied. They rejected also my lawyer’s demand of giving me a copy, stating that I had no right of getting one. Imagine that a person has written a book, but isn’t allowed to read it. This is so strange! The regime was like the one we were used to in Arab countries. It was a strange repressive authoritarian regime, just like the one we knew and were used to in third-world countries. It was unlike the freedoms we hear about in the United States. It is possible that you, in the West, in Britain for example, don’t know about these things, but the army and families rule in our Arab countries. Hence my ability to recognize authoritarianism when I see it. Unfortunately, Guantanamo is an authoritarian country within the United States. That is the reason. There is no binding law nor international law, and even US laws are not respected.

What do you think the impact of ‘The War on Terror’ and the imprisoning of people in Guantanamo Bay has been in countries like Mauritania, Afghanistan and Iraq?

I’ll give you an example. My family and I have nothing to do with this war. We are simple people who want to live in safe conditions, work and earn a living. We want respect. We do not wish slavery on anyone because we have nothing to do with US political, geopolitical and geostrategic interests. The US wants to control some countries; Russia wants to control some countries. We have nothing to do in all this war against terrorism. Unfortunately, simple people are getting killed in this war, and wars are waged against them. Their children, from both sides are being killed. I’ve said it and I will say it again; we have nothing to do with this war. Through this war, the United States wants to take over the world, but we, as people, have nothing to do with it. We are trying to live peacefully in democracy and freedom. Whoever wants to resort to violence has to deal only with the law. Whoever wants peace and wants to express his opinion, no matter how extremist it is, even if they express a distrust of government, has the right to do so within the context of freedom of speech. We want this, the same way it is happening in all the states compliant with the rule of law and human rights. This war against terrorism is a war that honestly benefits terrorism and extremism. This is obvious and the numbers are obvious. Before September 11, terrorism did not exist. However, things changed after the occupation of Iraq because terrorism feeds on violence and grows in a violent environment. Where there is violence there is terrorism.

One of the first executive orders Donald Trump signed was to keep Guantanamo open and he indicated he wanted to send more people there. What do you think of this policy?

President Donald Trump is elected by the American people. From what I know, and I might be mistaken, he is responsible for observance of the law and the US Constitution. The law and the US Constitution forbid illegal imprisonment. Just search the internet and go through the reports of the US State Department, where it condemns the states that violate and disrespect the law, including Mauritania. I have read a report about Mauritania. It is nice that the US says that it opposes the violation of law and people’s imprisonment outside the legal framework. However, it is unacceptable that the US announces that it will be ignoring the law and that it does not respect it. If you belong to a certain race or religion, the US does not respect the law, and so it won’t bring you before a court of law. This is so unfortunate. However, and I say it again, the Americans have elected their president, and they are paying for it. This is unfortunate for people who are calling for peace and for human rights. It saddens me that the greatest nation in the world, like the United States, disdains the law. All the little totalitarian, or rather authoritarian, countries are happy with that. They would tell us: you see? We told you democracy was useless. Look at the United States, the greatest country in the world. It does not respect democracy or human rights, so why would you ask for them from us? The United States is an important and powerful country, if not the most powerful in the world. What the United States does and says makes a difference because it can defend human rights, for it has the means that no other country has. As a person who has lived and interacted with the kind American people and who wishes the American people well, it saddens me that the United States has reached this level of disdaining human rights and ignoring freedom and democracy.

What is the one thing you would want our readers to take away from what happened to you?

Readers should know that law and democracy are valid and useful, and that despising democracy and human rights is invalid and inadmissible. Why am I saying that? Because the US said it would be torturing me until I confessed, then it would take me to court and prosecute me. I was sent to be tortured in Jordan, Afghanistan and Guantanamo, and yet it was unable to bring me before the court. The US did all that so it could collect proof of violence and sentence me in court. The United States failed. Why? Because a state of law is the only one that is valid. The executive branch in a state should not sentence people without trial.

Second, I tell readers: no matter what culture you’re from, no matter what is your religion or colour, you can be subjected to this injustice. People who stood by my side were from all colours and cultures, and people who tortured me were from different cultures and colours, including Muslims, Americans, Christians, Jews, and from all parties. I say it again, democracy, human rights and trials are useful and provide security, while all else brings only insecurity and regression.

Become a Friend of PEN International today and help us continue our vital work in supporting writers around the world who are being silenced. Starting at just £5 a month.