Who ranked you among poets?

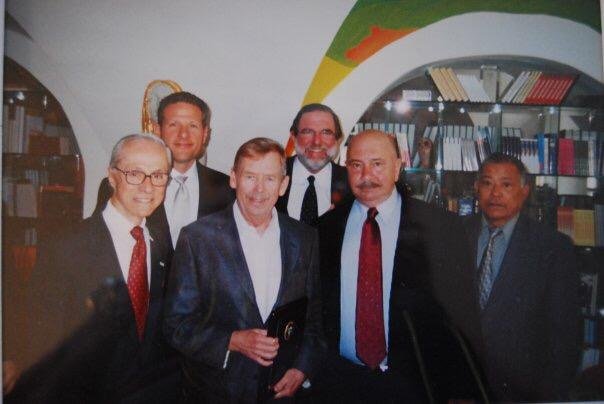

Angel Cuadra Next To Vaclav Havel With A Delegation Of Pen Cuba In Exile

A century of PEN’s defense of imprisoned poets

In the 1930s, two of the first PEN International cases were poets: Jacques Roumain and Federico García Lorca. PEN campaigned for Lorca after he was detained on the first weeks of the Spanish Civil war, and cruelly assassinated by a fascist squad.

The process to defend the Haitian poet Jacques Roumain started in New York, where Langston Hugues and others created the “Committee for the Release of Jacques Roumain.” Roumain was the founder of the Haitian Communist party and had been imprisoned as a leader of the movement against the United States’ occupation of Haiti. When Henry Scidel Canby traveled to Barcelona to attend the 1935 PEN International congress as delegate of the American PEN Club, he was tasked to present a motion about Roumain. Supported by Henrietta Leslie from English PEN, the motion was adopted unanimously thanks to the diplomatic wisdom of Canby, thus the first PEN resolution in defense of an imprisoned writer was approved at the Catalan congress.

When the Writers in Prison Committee of PEN International was created at the 1960 PEN International Congress in Rio de Janeiro, there were several poets in the first case list added as an annex to the minutes of the congress. Among them, the Albanian Musine Kokalari, who was the first woman writer to be published in Albania when she issued her first collection of poems My Old Mother Tells Me. She was sentenced to twenty years in jail for being an ‘enemy of the people’, after she had sent a letter to the Allied Forces based in Tirana, calling for free elections and freedom of expression.

In 1963 PEN campaigned for Russian poet Joseph Brodsky. The transcription of the interrogation by the judge at the 1964 trial that sentenced him for “parasitism” is very telling of the depth of the gap between the state willingness to control expression and the freedom of the poet:

Judge: In general, what is your specific occupation?

Brodsky: Poet. Poet-translator.

Judge: And who said you’re a poet? Who ranked you among poets?

Brodsky: No one. (Unsolicited) Who ranked me as a member of the human race?

Judge: Did you study for this?

Brodsky: Study for what?

Judge: To become a poet. Did you attend some university where people are trained … where they’re taught…

Brodsky: I didn’t think it was a matter of education.

Judge: How, then?

Brodsky: I think that … (perplexed) it comes from God…

Judge: Do you have any petitions for the court?

Brodsky: I’d like to know why I was arrested.

Judge: That’s a question, not a petition.

Brodsky: Then I have no petitions.

After he was expelled ("strongly advised" to emigrate) from the Soviet Union in 1972, in his exile Brodsky was actively supported by PEN America, Swedish PEN and others. Polish PEN welcomed him in Warsaw a few months after the fall of the communist regime:

PEN International celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1996 with the publication of a selection of texts by imprisoned writers. The book, edited by Siobhan Dowd, under the title This Prison Where I Live, included texts from poets like the Peruvian Cesar Vallejo, the South Korean Kim Chi Ha, the Russians Varlam Shalamov and Irina Ratushinkaya, the Turkish Nazim Hikmet, the Malawian Jack Mapange and others. Greek poet Yannis Ritsos contributed with his poem Broadening:

We were to stay here, who knows how long. Little by little we lost track of time, of distinctions — months, weeks,

Days, hours. It was fine that way. Below, way down, there were oleanders; higher up, the cypress trees; above that, stones.

Flocks of birds went by; their shadows darkened the earth. That’s the way it happened in my day too, the old man said. The iron bars

were there in the windows before they were installed, even if they weren’t visible. Now

from seeing them so much, I think they’re not there — I don’t see them.

Do you see them? Then they called them guards. They opened the door,

pushed in two handcarts full of watermelons. The Old man spoke again:

Hell, no matter how much your eyes clear up, you don’t see a thing. You see the big nothing, as they say: whitewash, sun, wind, salt. You go inside the house: no stool, no bed; you sit on the ground. Small ants amble through your hair, your clothes, into your mouth.

PEN has also campaigned for poets who started to write once imprisoned. This is the case of the Iranian Mahvash Sabet, who published her collection of poetry on the fifth anniversary of her incarceration. Arrested in 2008 for simply being a Baha’i, her intimate poetry of prison life has travelled the world:

Lights Out

Weary but wakeful, feverish but still fixed on the evasive bulb that winks on the wall, thinking surely it’s time for lights out, longing for darkness, for the total black-out.

Trapped in distress, caught in this bad dream, the dust under my feet untouchable as shame, flat on the cold ground, a span for a bed, lying side by side, with a blanket on my head.

And the female guards shift, keeping vigil till dawn, eyes moving everywhere, watching everyone, sounds of the rosary, the round of muttered words, fish lips moving, the glance of a preying bird.

Till another hour passes in friendly chat, in soft talk of secrets or a sudden spat, with some snoring, others wheezing some whispering, rustling, sneezing – filled the space with coughs and groans, suffocated sobs, incessant moans – You can’t see the sorrow after lights out. I long for the dark, total black-out.

Arguably one of Eritrea’s finest women poets, a radio presenter, and short-story writer, Yirgalem Fisseha Mebrahtu suffered six years of arbitrary arrest in the country’s most notorious military prison. In February 2009, the educational station Radio Bana, where Yirgalem had worked, was raided by the military who took into custody more than 30 staff members and journalists associated with the radio station. Majority was only released after four years, but Yirgalem and five others were released after six years and without ever facing trial. While in custody, she became an iconic and symbolic figure of the resistance to the Eritrean regime. Her image presided the founding of PEN Eritrea in exile. The Eritrean delegate Dessale Abraham Berekhet raised her picture calling for the creation of the new center at the PEN International Congress in Bishkek in 2014.

Today, Yirgalem Fisseha Mebrahtu is part of the Writers in Exile programme of German PEN and, with the support of poetry festivals and the network of PEN Centres, her voice brings the sound of Eritrean resistance around Europe: «I received honour, recognition, and overall support thanks to PEN network. Thanks to the advocacy and promotion of PEN International I received emergency fund from PEN Netherlands while I was in Uganda; resettled in Germany and received a scholarship from Writers in Exile Program of German PEN—Yirgalem shares during an interview— I feel this is a reparation to the sufferings I have endured in my home country, as the very fact of becoming a writer is an offense in the eyes of the regime. »

Poets and their imprisonment have tragically shaped the life of PEN International during the first century of the organization. One month ago, Cuban poet Ángel Cuadra, who had spent 15 years in prison under Fidel Castro’s regime and was the founder of Cuban Writers in Exile PEN, died while exiled in Miami. May his smile remind us of the unbreakable chain that unites the memory of PEN’s commitment with imprisoned poets since the early case of Haitian poet Jacques Roumain.